In the History of Hertfordshire by John Edwin Cussans (published 1870-81) the inscriptions on the Forsyth tomb were recorded, but only partially. They are now almost impossible to read and so it is very fortunate that in 1913 a member of the East Hertfordshire Archaeological Society, Mr Ernest Squires of Hertford, took the trouble to record them in full and that his work is available in volume 5, part 2, of the Transactions of the society [available at the Hertfordshire County Archives, and elsewhere]. The full text is as follows-

On the south side: IN THE VAULT BENEATH ARE DEPOSITED THE REMAINS OF TWO AFFECTIONATE NIECES, DAUGHTERS AND COHEIRESSES OF FENN NEALE, ESQ., OF MARCH, IN THE ISLE OF ELY, DECD. ELIZABETH THE BELOVED WIFE OF THOMAS FORSYTH, ESQR. OF EMPINGHAM IN THE COUNTY OF RUTLAND: WHO DIED THE 24TH OF DECEMBER 1799: AGED 55 YEARS [should be 56 years]. TO PRESERVE HER MEMORY AND HIS AFFECTION THIS TOMB IS ERECTED.

In her whose Relicks mark this sacred Earth, Shone all domestick and all social Worth; Without one Thought but did from virtue flow Without one wish but such as Heav’n might know The mildest Temper ever blest with Ease, Of gentlest Manners, ever form’d to please: Fond to oblige, too gentle to offend Belov’d by all, to all the Good a Friend Unblam’d thro’ Life, lamented in the End These are thy Honours.

SUSANNAH, THE WIFE OF MR. THOMAS CLEMENT, CITIZEN OF LONDON: WHO DIED THE 11TH OF OCTOBER, 1772: AGED 29 YEARS.

Equal as Age advance’d, her Virtues grew And Heav’n her Aim still nearer shone in View. The Meek will he guide to Judgement, and them will he teach his way Learn from this Tomb that what thou valu’st most And Sett’st the Heart upon, may soon be lost! Boast not thyself of To-morrow, ‘Our Times are in thy Hand, O God.’

On the north side: THOMAS FORSYTH ESQ: OF UPPER WIMPOLE STREET, LONDON; DIED 7TH AUGUST, 1810; AGED 66.

Of considerable capacity, of extreme prudence, and of inflexible integrity, He attained to affluence, which he distributed with liberality. Not in personal ostentation, but with extensive beneficence. To the poor he was charitable; to the afflicted humane; to the perplexed a safe guide; to unprotected youth a generous patron. Open and direct in his own nature, he was unsuspecting of others: Towards failings from which he was himself exempt, most liberal and indulgent. Of such benignity of disposition. & suavity of manners, As to command the affection of his friends, and conciliate the good will of all men. In every private as in every public duty of life most exemplary; As a husband most tender and affectionate: As a Christian unaffectedly pious: As a moralist irreproachable: as a friend inestimable: He lived without having encountered the assaults of envy or malice, And he died beloved and lamented by all to whom he was known. But most especially by his afflicted Widow

JANE FORSYTH

who impressed with unalterable affection and pious gratitude, has caused this marble thus to be inscribed. To the memory of the best of husbands.

HERE LIKEWISE ARE DEPOSITED THE REMAINS OF JANE, RELICT OF THE ABOVE THOMAS FORSYTH ESQUIRE, DIED NOV. 16TH 1835.

Fenn Neale

The first person mentioned in the inscription is Fenn Neale. He was baptised at March on 5 August 1709. His father Thomas Neale had married Elizabeth Fenn at Wisbech on 15 February 1708.

Shortly before Fenn was born a school was established at March under the 1696 will and codicils of William Neale of March, who died in 1697. William seems not to have had any children, but his will mentioned nephews John Neale of Mileham, clerk, and William Neale, son of John Neale late of Wisbech, merchant. Also mentioned were William Neale, son of John Neale of Mileham, and kinsman John Neale of Walsham, clerk. Whether any of these Johns or Williams was the grandfather of Fenn Neale is unknown but clearly not impossible. The school became March Grammar School and still exists as the Neale-Wade Academy.

Another will was made at this time by a March man called Neale. This was John Neale, who called himself a merchant. His will was made in August 1700 and proved in the following April by his widow Elizabeth. A marriage of John Neale and Elizabeth Whinnel at March in 1684 looks right. There were three children, all of whom were under 21 when the will was made. They were Thomas, John and Elizabeth. Clearly this Thomas cannot have been Fenn’s father but the use of the name in the family suggests that there was a connection.

Fenn Neale married Elizabeth Gamble at Doddington on 7 July 1730 but she died (apparently childless) early in 1736 and was buried at March on 25 January. The rector of Doddington for the time being was one of those charged by William Neale with responsibility for appointing the schoolmaster for his new school.

Fenn (of March in the Isle of Ely) then married his second wife Susanna Watts (of Westwood in this parish) at St John the Baptist, Peterborough, on 20 December 1740. There is no evidential record but it seems as if Susanna was a widow when she married Fenn. On 9 September 1709 Susanna, daughter of Ralph and Elizabeth Morris of Carpenter Court, Holborn, was baptised at St Sepulchre’s, the church closest to the Old Bailey. The baptismal register gives her date of birth as 14 August. Susanna Morris married John Watts of Westwood at St Benet and St Peter, Paul’s Wharf, in the City of London, on 30 January 1729. This couple had two children who died in infancy and were buried at Peterborough. John Watts himself was buried there in 1735.

Records of their baptisms have not been found but, if the ages at death inscribed on the Forsyth tomb are correct, Fenn and Susanna’s first daughter, Susanna, was born in 1742 and their second, Elizabeth, in the following year. Susanna Watts was living at Westwood, in the parish of Longthorpe, at the time of her wedding and it is likely that the two daughters were born at Westwood.

Fenn made his will on 10 July 1743, shortly after the birth of his daughter Elizabeth (whom he described as an infant), and he was buried at Peterborough on 3 November 1747. The will was proved in the Consistory Court of Peterborough on 21 November 1747. It bequeathed to his wife a life interest in his estate, which consisted primarily of two properties at March: the first was a house and land called Elwyn Orchard and the second was five acres at a place called Mill Hill. There are several streets in modern March with names including the word Elwyn and there is also a Mill Hill Lane. (In the context of this story it is a remarkable coincidence that Elwyn is Welwyn without the initial W.) Subject to their mother’s life interest, the will did make his two daughters his coheiresses, as the inscription states.

Fenn’s widow Susanna married her last husband, widower Joseph Chatteris of Longthorpe, at Cotterstock on 27 September 1748 but the marriage was short-lived. Susanna was buried at Peterborough on 15 March 1750, leaving her two daughters as orphans aged under eight but with the benefit of equal shares in their father’s estate.

There is one other rather older grave in the old churchyard featuring the surname Neal. Although the spelling is different the possibility remains that there was some connection with the family of Fenn Neale. Those buried were William Neal, who died aged 77 on 15 July 1751, and his wife Mary, who died aged 63 on 18 November 1743. They had eight children baptised at Ayot St Peter between 1706 and 1720. One of their sons, Robert, and his wife Hannah, had five children baptised here between 1750 and 1759.

The St John family

In his will Fenn Neale described himself as ‘of Westwood Neare Thorp Northamptonshire, farmer.’ The parish of Longthorpe (often abbreviated to Thorpe) is now incorporated into the city of Peterborough but in C18th was quite separate from it. The big house in the parish is grade I listed Thorpe Hall, which was built during the Commonwealth period by Oliver St John (Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas under Oliver Cromwell) on land taken from a monastery sacked during the Civil War. It still stands and is now a Sue Ryder Home. It is believed that Fenn Neale was farming land owned by the St John family of Thorpe Hall which came into his hands with his marriage to Susanna Watts of Longthorpe.

Another member of the St John family, Frances, lived at what is now called Danesbury but was at this time called St John Lodge, Welwyn; it was finished in 1778 by the daughter-in-law of the 10th Baron St John and inherited by Frances, a spinster, in 1786. In her will dated 6 April 1793 Frances appointed Thomas Forsyth of Upper Wimpole Street, London, as her sole executor and residuary legatee and directed that she was to be buried in the St John family vault at Thorpe, which is located at St Botolph’s church, Longthorpe. There is a tablet in the church with this inscription-

In a vault beneath this Church are deposited with those of her ancestors and relatives, the remains of Mrs Frances St John of St John Lodge in the county of Hertford, spinster, the last surviving daughter of Sir Francis St John, late of Thorpe, Baronet, who departed this life on May 19, 1794, aged 82 years. To perpetuate the remembrance of virtues which dignified human nature, this monument to her respected memory is dedicated by Thomas Forsyth, Esquire, her executor. All that e’er graced a soul from heaven she drew, And took back with her as an angel’s due

Evidently, Thomas Forsyth knew Frances St John well and it is more than likely that she knew Rev Charles Chauncy, a local clergyman of illustrious lineage who lived in an equally big house nearby, namely Ayot Bury (which was the rectory of Ayot St Peter at this time). The interesting question is: how did Thomas know Frances? It seems as if the answer may really be that it was his wife, Elizabeth, and her Neale family who provided the link. It would unduly encumber this narrative to explore fully the relations between the Neales and St Johns but it seems more than likely that Frances St John would have acknowledged the Neale sisters as kinswomen, possibly rooted as far back as the C16th Bedfordshire marriage of Henry St John and Jane Neale, whose wills were proved on 28 June 1598 and 7 September 1618 respectively.

It seems as if it was these connections that led to Susanna Clement being buried at Ayot St Peter, which in turn led to the three later burials and the construction of the tomb.

Nieces

Following their mother’s death the girls must have been raised by an aunt or uncle.

According to his will, Fenn Neale had a brother John and a sister Elizabeth. John Neale’s baptism has not been found but Elizabeth’s was on 27 February 1718 at March. It is not known whether John Neale married but Elizabeth certainly did. Her first husband was Daniel Cooper of Holywell-cum-Needingworth and the wedding at March took place in March 1742. Daniel had died before 16 June 1761 when Elizabeth Cooper (a widow) married Robert Nelson of Wisbech in her then parish of Holywell-cum-Needingworth. Adjacent to the Forsyth tomb is a fine but illegible headstone with a footstone recording Joseph Nelson 1764 and Elizabeth Nelson 1770. The Ayot St Peter burial register gives us the information that Joseph Nelson, a minor, was buried on 5 December 1764 and Elizabeth Nelson, ‘a minor from London,’ was buried on 21 March 1770. It is believed that these were the children of Fenn Neale’s sister Elizabeth Nelson, who was probably a witness at the marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to Thomas Forsyth in 1769. Confusingly there was another Elizabeth Nelson who was a spinster living in Wimpole Street. Just before she died in 1786, Elizabeth made a will in which she appointed as her executors the husbands of the two nieces, Thomas Forsyth and Thomas Clement. The will makes clear that her branch of the Nelson family hailed from Cottingham, Northamptonshire, but also had strong connections in St Marylebone. It is likely, but not proven, that Robert Nelson of Wisbech was a member of this same family. (Immediately next to the Nelson headstone and footstone there is a very similar memorial to Thomas Willet, a servant, buried on 28 July 1766 and Margaret Willet, a widow, buried on 23 March 1767. It seems likely that this couple worked in the household of Elizabeth Nelson and that Thomas Forsyth bore the costs associated with all four burials.)

It is perfectly possible also that the two girls were raised by a brother or sister of their mother Susanna. She did not leave a will and therefore there is no direct evidence one way or the other. It is also quite possible that Frances St John helped with their upbringing, in which case they might have spent some of their time at her house at Welwyn.

It can be assumed that the two sisters were indeed both ‘affectionate’ and ‘nieces’ but the identity of the person or persons who raised them cannot now be established.

Millinery and marriage

Although nothing is known for certain about the education or upbringing of Susanna and Elizabeth Neale, it seems more than likely that much of their time following their mother’s death in 1750 was spent in the fashionable parish of St George’s, Hanover Square, in the West End of London, where they were certainly living in 1769.

Their uncle John Neale had moved from March to London and become a hatter with premises in New Bond Street. It is not known when he made the move or whether he was the first hatter in the family or was instead following in the footsteps of previous generations of Neales. It is recorded that in 1771 John Neale was a victim of theft, and in 1776 he became bankrupt. As will emerge, his involvement in the trade of hat making had important ramifications for his two nieces and their wider connections.

By 1765 Elizabeth Neale was sufficiently well established as a milliner at Bartholomew Close in the City of London to take on an apprentice named Ann Hodgson. It is likely that she was in business with her sister Susanna because the apprenticeship was in the name of Elizabeth Neale & Co. Although by 1769 the firm was established in the West End it retained a place of business in the City because in November 1772 another apprentice called Lucy Blackburn was taken on at Watling Street. As we shall see, Susanna had died a month earlier and 15 Watling Street was her matrimonial home.

The younger of the sisters married first. On 3 October 1769 Elizabeth Neale married Thomas Forsyth at St George’s, Hanover Square. They were both ‘of this parish.’ The four witnesses included (as we have seen) one or other of the two Elizabeth Nelsons. The marriage was ‘by Licence from the Archbishop.’ It was fashionable for people of high standing, who did not wish to attend to hear their banns read out, to obtain a special licence. Normally these were from the diocesan bishop but the very grandest secured theirs from the Archbishop of Canterbury at Lambeth Palace. In a notice of the marriage in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette of 12 October Thomas was described as ‘of Brook Street’ and his bride was described as ‘Miss Betty Neale of New Bond Street.’ In 1778 Thomas Forsyth, gent., and his wife, a milliner, had premises at 100 New Bond Street. It is likely that these were the premises from which John Neale had traded before his bankruptcy and that Elizabeth had taken over the business from her uncle. In the same year, 1778, Catherine Woodcock started up a milliner’s shop in Norwich. She advertised herself as from ‘Mrs Forsyth’s New Bond Street.’ Unfortunately she, like John Neale, went bankrupt a few years later. It was, of course, notoriously difficult for traders to get their aristocratic patrons to pay their bills.

Just under two years later on 27 July 1771 the elder sister, Susanna Neale, married Thomas Clement at St George’s. She was ‘of this parish’ but her husband was of the parish of St Leonard, Foster Lane, in the City of London.

The first burial

Sadly, the marriage of Thomas and Susanna Clement was to last only briefly. Susanna died in October 1772, very possibly in child-birth and almost certainly at the matrimonial home at 15 Watling Street. The death was no doubt sudden and unexpected. Certainly there was no will, and presumably her half share of her father’s estate passed to her husband.

The Ayot St Peter burial register records that on 15 October 1772 ‘Susanna Clement from London’ was buried by Rev Charles Chauncy (1733-1804), who was rector of Ayot St. Peter from 1766 until his death and had previously served as curate there from 1758 until 1766. Clearly it was this burial which started the sequence and created the link for the three later burials.

After such a short marriage Thomas Clement probably had no strong feelings about where his wife should be buried, and it seems likely that the choice of Ayot St Peter was made by her sister and brother-in-law. If Thomas Forsyth knew Frances St John well enough to be appointed as her sole executor and residuary legatee, he and his wife had no doubt visited her at Welwyn, and probably through her had become acquainted with Charles Chauncy. Susanna’s old connections in March and Longthorpe had apparently ended some years previously and there was the future prospect of visits to St John Lodge, when the old churchyard could be visited at the same time. It must all have seemed very sensible to Thomas and Elizabeth Forsyth.

Thomas Clement

The inscription describes Thomas Clement as a citizen of London, indicating that he held the Freedom of the City. On 22 November 1763 it was ordered that this honour be granted to Thomas Clements ‘by redemption in the Company of Merchant Taylors.’ Despite the spelling of the surname it is believed that the grantee was Thomas Clement. If this is the relevant grant, it gives us the important information that Thomas Clement was the son of another Thomas Clement of Ingleby in the old North Riding of Yorkshire, who was a farmer but deceased by 1763. This would make Thomas one of the very long line of young men who have gone up from the country to London to seek their fortunes. He must have been born early in the 1740s. There were four villages in the North Riding with Ingleby as the first half of the name. Ingleby Barwick, on the south side of the River Tees and close to Stockton-on-Tees, is the likeliest of the four to be the ancestral village, given that (as we shall see) a granddaughter made her home at Stockton (having, perhaps, inherited property in the neighbourhood).

Following the death of his first wife he married Mary Linthorne ‘of the parish of Richmond in the county of Surry spinster’ on 16 September 1775 in the church of St Vedast, Foster Lane. Mary was another milliner; on Thursday 9 September 1773 Mary Linthorne of Richmond, Surry, milliner, took on Hannah Cleaver Parnell as her apprentice.

There is a record of insurance taken out on 16 July 1790 by Thomas Clement of 15 Watling Street, dealer in crepe and tiffany. His address was on the south side of the old Roman road near to its western end at St Paul’s Churchyard. This part of Watling Street was destroyed in the Blitz and not rebuilt. Approximately where no. 15 stood there is a bust of Admiral Arthur Phillip RN, who commanded the First Fleet transporting convicts to Botany Bay and was the first Governor of New South Wales. Thomas Clement’s trade in materials was consistent with membership of the Merchant Taylors.

When he made a will on 19 December 1794 he must have known that he was dying. His will expressed his desire to be buried in the church or burying ground of the parish where he died. He was duly buried on 30 December 1794 in the old vault at All Hallows, Bread Street, which stood on the corner of Watling Street and Bread Street until its demolition in 1878 and was the church closest to the deceased’s home. No age at death was recorded. The will was proved at the nearby Prerogative Court of Canterbury, Doctors’ Commons, on the following day on the oaths of John Pearkes of St Paul’s Churchyard, gauze weaver, Joseph Langhorn of Watling Street, warehouseman, and his widow Mary Clement.

In his will he described himself as a warehouseman of Watling Street in the City of London. He was the owner of the freehold of 15 Watling Street and he gave a life interest in it to his widow Mary. He mentioned only one child, his daughter Susanna Clement. Born in 1776, she was not yet 21 in December 1794 and was the daughter of the second wife named in memory of the first. She married Thomas Warren, a Birmingham merchant, at Fulham on 5 December 1795. Her husband died in 1798; under his will made a year earlier his entire estate passed to Susanna, who was sole executrix. On 9 August 1804 at Richmond in North Yorkshire the widow Susanna Warren married Matthew Whitelock. The Whitelocks lived in Frenchgate, Richmond, where Susanna died in 1844 and Matthew died 14 years later, leaving an estate of £300. Susanna had no children.

Thomas Clement’s will also mentioned a brother William and sisters Mary Cross (a widow) and Margaret Clement. There were three nieces called Jane, Susanna and Rebecca Clement, who were William’s daughters. Whereas no records have emerged concerning Rebecca, a fair amount is known about Jane and Susanna. Jane Clement was born in 1762 and married Samuel Fish, a Clerkenwell tobacconist, in 1798. Samuel was a widower. His first wife was Elizabeth Yates, with whom he had four daughters called Elizabeth, Ann, Rebecca and Caroline. Ann married Henry Bennett but her three sisters did not marry. With his second wife Jane Samuel Fish had two sons, Samuel Charles Cross Fish and Philip Thomas Fish. Samuel Fish died in 1848 and left his entire estate to his children of the two marriages. Susanna Clement was born in 1770, she never married but made her home at Stockton-on-Tees – across the river from Ingleby Barwick, where her grandfather probably lived, and not so very far from where the other Susanna (Whitelock) was living at Richmond. Susanna Clement died in 1828 and left her entire estate to her two nephews, her sister Jane’s sons Samuel and Philip Fish.

Thomas Clement also had a nephew called Thomas Cross. He was the son of Mary Cross (née Clement) and her husband Jonathan, who were married in 1755; Thomas was born in 1757; his father Jonathan died in 1781. There must have been a third sister who married a man called Wright because the 1794 will named three further nephews – Thomas, William and Nathaniel Wright.

Thomas Clement probably attended the burial of his first wife Susanna at Ayot St Peter in 1772, possibly accompanied by one or more of his siblings; he may have returned for occasional later visits. He had died before the tomb was erected in 1800 and so he never saw the inscription mentioning him and his first wife. It seems very unlikely that any of the descendants of his second marriage or of his siblings’ marriages (including the two Susanna Clements) have ever visited the old churchyard to view the tomb.

The second burial

Elizabeth Forsyth died on 24 December 1799 at her husband’s seat at Empingham, Rutland. There was no will but presumably what remained of her half share of her father Fenn Neale’s estate passed to her husband. It will have been agreed between them that she should be buried alongside her sister at Ayot St Peter, and the burial register records that her husband was living and that her remains were brought from Empingham to the churchyard and buried there by Rev Charles Chauncy on 3 January 1800. Elizabeth had died without issue at the age of 56.

Thomas Forsyth then made arrangements for a vault to be constructed and a tomb made to accommodate the coffins of his wife and sister-in-law, with the intention that he should join them there upon his own death. At this time he will have settled upon the wording of the inscriptions on the south side of the tomb. The burial register records that the tomb was brought from London on 1 June 1800 and was ‘entirely finished setting up’ on 17 June. The tomb must have been brought from the stonemasons’ premises in prefabricated sections in a number of wagons, and the men who excavated and lined the vault and built the tomb over it in the course of 17 days must have stayed in the parish – perhaps at the Horse and Jockey inn on Ayot Green (now 5 Ayot Green).

It seems likely that Susanna Clement’s burial in 1772 was initially marked by a headstone and footstone similar to those still standing on the nearby graves of Joseph and Elizabeth Nelson and Thomas and Margaret Willet and was on the site of the tomb. In any event her coffin must have been disinterred for reburial in the vault alongside her sister’s.

The tomb (like the headstones and footstones) will have been very expensive to purchase, transport and assemble. It will have seemed quite exotic in the simple country churchyard of Ayot St Peter, and it still looks imposing nearly 220 years later. It was the first of the three fenced tombs in the old churchyard to have been installed.

Thomas Forsyth

Despite the fact that he was a man of very considerable means the lineage of Thomas Forsyth has proved elusive. He was 66 when he died in the summer of 1810 and therefore born in about 1744. There is a record of the baptism of a Thomas Forsyth, son of John and Mary Forsyth of Field Lane, Holborn, on 17 April 1747 which could be right, but it is not possible to be sure.

Research into the life of Thomas Forsyth is complicated by the fact that there were two other men of the same name active in London during his lifetime who appear in contemporary records.

First there was a peruke maker with premises in New Bond Street, who joined a Freemasons lodge in 1763 and subscribed to a book on the craft in 1769. He married Ann Wilson on 27 April 1779 at St Martin in the Fields. By 1781 he and his wife had died. He could have been the boy baptised in 1747. In a history of Pierremont Hall, Broadstairs, published in 2006 Ann Wilson was mistakenly named as the wife of the Thomas Forsyth buried at Ayot St Peter.

Secondly, there was a Thomas Forsyth, son of William Forsyth and Jean Phyn, who was born at Huntly, Aberdeenshire, and emigrated to Quebec to work in the Montreal office of the London firm of Phyn, Ellice & Co. His younger brother John (b 1762) followed him to Canada. Given his Canadian connections he was probably the Thomas Forsyth who was one of the subscribers who funded the publication in 1789 of a book of letters of Lt. Thomas Auburey entitled Travels through the interior parts of America. In 1806 John Forsyth was a member of a committee established to raise funds for the erection of a column in Montreal to commemorate the life of Lord Nelson. Thomas Forsyth was part of the London end of this enterprise. He had been taking an interest in Nelson for some time and in 1802 had written to the Hero of the Nile to enquire which of the numerous images of him was the best likeness. Nelson wrote to Forsyth at 26 Surry Street, Strand, from Merton on 2 February 1802 with the opinion that ‘a little outline of the head sold at Brydon’s Charing + is the most like me.’ This pencil sketch was made by Simon de Koster in 1800. On 20 October 1810 (over two months after the death of the Thomas buried at Ayot St Peter) he became the first chairman of the Canada Club. This Thomas Forsyth retired from business in 1816.

The name Forsyth is Scottish, and Thomas was among several wealthy London Scots called Forsyth who, by virtue of their donations, were ‘governors’ of the Scottish Hospital (an institution which was in Crane Court, off Fleet Street, from 1781 to 1843 and provided help to distressed London Scots). Their names and addresses were: David of New Bond Street; James of Mark Lane; Thomas of Wimpole Street; and William and William jnr. of Kensington. David Forsyth’s address is interesting; Thomas also had premises in New Bond Street. William Forsyth was a founder of the Royal Horticultural Society and is commemorated in the plant name ‘Forsythia.’ He was appointed ‘Gardener to the King at Kensington’ in 1784 and produced a plan for Kensington Gardens in 1787. He wrote A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees; In which a new method of pruning and training is fully described, which was published in 1802. There is extant a first and only large format edition of this book with the words ‘Thomas Forsyth, Esq. From the author.’ inscribed on a front blank, which suggests a strong connection between William and Thomas. William’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography states that he was born at Oldmeldrum, Aberdeenshire, in 1737, went to London in 1763 and died in 1804. In 1811 (the year after Thomas’ death) ‘Forsyth W. esq.’ was listed as an occupier of 4 Upper Wimpole Street with Thomas’ widow. Given the moral climate of the time it can be assumed that this gentleman was a member of Thomas’ family. It seems likely that he was William jnr. of Kensington, son of the gardener.

If, as is clearly possible, William snr. was a brother or half-brother of Thomas they probably travelled to London together when Thomas was about 19. If so, Thomas might have chuckled at Dr Johnson’s famous aphorism that ‘the noblest prospect which a Scotchman ever sees, is the high road that leads him to England!’

Nothing is known of his education. Many Forsyths attended Aberdeen University but Thomas does not appear to have been among them. Nor does he appear to have attended either Oxford or Cambridge university. He did, however, become a solicitor with an office at 100 New Bond Street and must therefore have been a pupil at one of the Inns of Chancery attached to Lincoln’s Inn. In his time solicitors were those qualified to deal with matters falling within the jurisdiction of the Court of Chancery; this was known as equity and was distinct from the common law jurisdiction of the Courts of King’s Bench and Exchequer, where attorneys were the equivalent of solicitors. As a solicitor he was well equipped to be a steward of a landed estate and a trustee and executor and, as we shall see, this is how he earned his living.

He was also actively engaged in property speculation, often in partnership with others. During his first marriage he purchased land at Pierremont in the Isle of Thanet on which he built a fine house in a landscaped park, which was finished in 1791-92, is grade II listed and currently used as council offices. Initially called Forsyth’s Villa and apparently unkindly dubbed Forsyth’s Folly by Lady Fitzherbert, Pierremont Hall was designed in the offices of Samuel Pepys Cockerell (1753-1827) where much of the detailed work on the project was carried out by Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820). Latrobe was with Cockerell between 1787 and 1790. He emigrated to the United States, where he designed no less a building than the US Capitol in Washington, DC.

In a short notice of his death in the Gentleman’s Magazine it is recorded that he was for ‘many years agent to the estate of Sir Gilbert Heathcote, Bart.’ There were in fact several Heathcote estates in Rutland and Lincolnshire; his involvement with them and their owners had begun by at least 1774, during the time of the third baronet, who died in 1785 and was succeeded as fourth baronet by his son (1773-1851).

Although not named in the third baronet’s long and complicated will, Thomas was one of the witnesses to its execution on 22 July 1774 and also a witness to two of its several codicils. During the minority of Sir Gilbert junior Thomas Forsyth was de facto the young man’s guardian. In 1788 the owner of the Folkingham estate in Lincolnshire got into financial difficulties and the fourth baronet (no doubt on the advice of his steward) purchased the estate. A local history published in 1825 records that Folkingham ‘began gradually to assume a better appearance and, under the management and direction of the late Thomas Forsyth, esquire, most of the new buildings were erected, and the different alterations and improvements were made.’ Thomas definitely lived in the village of Folkingham for some of the time when he was steward of the Heathcote estates.

In a Compendium of County History – Rutland he is listed as having his seat at Empingham; the same list shows Sir Gilbert Heathcote with seats at Normanton and Stretton. Normanton Hall was the principal Heathcote residence; although it has been demolished its chapel still stands, but nowadays right on the shore of the man-made reservoir called Rutland Water. It is believed that Thomas’ seat at Empingham was Prebendal House, which was (like the rest of the village) part of the Heathcote estates and is today still a fine house standing close to the parish church. In May 1801, shortly after the death of his first wife, Thomas (who was ‘leaving off House-keeping’) arranged for a sale by auction of the contents of his house, which lasted over five days. The sale notice indicates that he and Elizabeth had maintained a very fine household. Despite the sale, Thomas was remembered as a householder some 16 years later; in Cary’s Itinerary of 1817 a coach which ran from Stamford to Oakham was described as passing ‘late Thos. Forsyth’s’ at Empingham at six miles. He continued to maintain a pied-a-terre in the village during his second marriage.

Empingham lies just to the west of the Great North Road and Folkingham is further north and east, on what is now the A15 between Bourne and Sleaford. On his presumably fairly frequent travels between these villages and London Thomas will undoubtedly have used the Great North Road. In doing so he will have passed both the entrance to St John Lodge (where it would be surprising if he did not occasionally rest for the night) and the turning into Ayot St Peter at the top of Digswell Hill.

Thomas was High Sheriff of Rutland in 1794 and was toasted as ‘the tenant’s friend’ at a dinner organised by Sir Gilbert Heathcote in October of that year at Stamford in Lincolnshire. It is known that the agency and the Heathcote connection lasted until shortly before Thomas’ death in 1810.

Thomas Forsyth was undoubtedly public-spirited: he was, for instance, a trustee of the North Luffenham Charity for the Poor; he supported the Scottish Hospital; and he took on a considerable number of executorships, including (as we have seen) that for Frances St John.

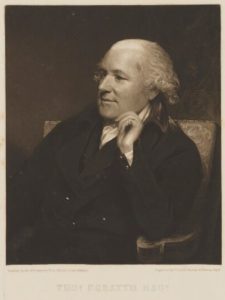

In the collection of the National Portrait Gallery are two mezzotints (catalogue numbers D37743 and D37750) taken from an engraving by Charles Turner (1773-1857) after a portrait by Sir William Beechey (1753-1839). The sitter was recorded simply as Thomas Forsyth Esq. but in May 2017 the NPG accepted that he was the person buried in the vault beneath the Forsyth tomb at Ayot St Peter.

On 9 July 1801 at St Marylebone parish church Thomas Forsyth married his second wife, Jane Martin. He was 56 and she 45 and not previously married. It is almost certain that she had for many years been a friend of Thomas and his first wife Elizabeth. Unsurprisingly there were no children. The marriage lasted only until Thomas’ death aged 66 at Earl’s Court on 7 August 1810. If William Forsyth jnr. was his nephew living at Kensington this place of death would be explained as occurring during a family visit.

Thomas and Jane Forsyth were noted for the generosity of their entertaining at Pierremont Hall. For example, there is a press report of Mrs Forsyth’s second concert and supper there on 28 September 1805, when at about 11.45pm 93 guests sat down to enjoy a cold collation after a full programme of music and did not go home until about 2 am. There is another report of ‘the elegant Mrs Forsyth’ patronising another lady’s concert at the theatre in Margate in 1803. In 1810 the house was remembered as ‘so celebrated during the life of the late Duchess of Devonshire, for the gay parties then held there.’

Thomas’ health may not have been particularly robust. In the first place, there were no children of his first marriage. Then, on 26 February 1784 he was admitted to St Thomas’ Hospital courtesy of Sir Gilbert Heathcote, who was a governor of the hospital. Finally, in May 1810 Pierremont Hall was advertised for sale ‘in consequence of the ill-health of the owner, Thomas Forsyth, Esq.’

His will dated 20 June 1809 made no mention of any children, siblings, nephews, nieces, cousins or other relations. It does mention extensive freehold and copyhold property interests in a number of counties. He had his leasehold house at 4 Upper Wimpole Street (which today is very much as he would have known it) and he also had his office at 100 New Bond Street (which was rebuilt in the 1880s but at this time belonged to James Paul Smyth, a wealthy perfumer, of whose 1797 will Thomas was one of the three executors). He left his entire fortune to his widow, who obtained a grant of probate at Doctors’ Commons on 25 August along with the other two executors, his friends James Abel (a City merchant) and Alexander Murray (a lawyer).

The third burial

Although his will was silent on the subject, Jane Forsyth will have known that her husband wished to be buried at Ayot St Peter and accordingly she arranged for her husband’s remains to be taken there, where the burial register records that they were interred ‘in his Vault’ on 14 August. By this time Rev Charles Chauncy had died but his son of the same name was the curate of the parish and conducted the burial service. Between 1808 and 1812 this unfortunate man had to bury no fewer than four of his own infant children.

At some point after the burial Jane Forsyth arranged for the laudatory epitaph to be incised in the circular marble panel affixed to the north side of the tomb. She will have chosen to describe her husband as ‘of Upper Wimpole Street, London’ and to omit mentions of all his property interests both inside and outside the capital.

Jane Martin and her family

Jane came from a large family with its roots in Southampton. They were well known in the town as proprietors of a sea-bathing establishment and assembly rooms which were patronised by fashionable society.

An earlier Jane Martin, who never married, was a noted milliner in Southampton in the first half of C18th. By the age of 28 Thomas’ future wife had moved to London, and on 7 February 1784 she became apprenticed to Mary Iggulden & Co., milliners, of the parish of St Ann, Soho. In 1799 Jane Martin, milliner, had premises at 92 Wimpole Street, apparently with a partner called Mary Haggard. It must be the case that Jane knew Elizabeth (or Betty) Forsyth, and thus her husband, through the millinery trade.

Jane was born in 1756 and was one of the five daughters of George Martin and his wife Elizabeth (Betty) née Brackstone born between 1748 and 1762. There was also a son called John, born in 1758. The eldest sister, Charlotte, married George Tarbutt and had six children. The second, Elizabeth, married Thomas Baker and also had six children. John and his wife Mary née Guy had at least two daughters – Harriet (who married William Lawrence) and Georgina (who married William Davy). By the time she died in 1835 Jane had many great-nephews and -nieces. The wills of family members shed light on all the connections.

Jane’s mother Betty Martin (of Southampton, widow) made her will on 14 December 1803. It names all her children and is thus a primary source. Thomas Forsyth was Betty’s sole executor and residuary legatee, and in a short postscript to the will she expressed her ‘particular request that [her] dear and respected friend….Thomas Forsyth Esqr. will accept of Twenty Guineas for a Ring in remembrance of me.’ In the portrait Thomas is shown wearing two rings on the little finger of his left hand, one of which is surely Betty’s mourning ring. This strongly suggests that it was his wife Jane who commissioned Sir William Beechey to make the painting between 23 January 1806 (when Thomas obtained probate of Betty’s will) and his death in August 1810.

Charlotte Tarbutt died in 1791 and her husband George died 10 year later, just before Jane’s marriage to Thomas Forsyth. Thomas was one of the executors appointed in George Tarbutt’s will dated 5 February 1801; another was Thomas’ friend James Abel. The will mentioned that George’s daughter Elizabeth was the wife of Thomas Vardon. Another daughter, Caroline, would marry George Maule and a third, Charlotte, would marry John Dugdale. Thomas Vardon lived at Battersea and had a large shareholding in Crowley Millington & Co., an iron and steel manufacturing and trading concern based at Winlaton, Co. Durham, and Greenwich. He had three sons and two daughters and died in 1809. George Maule was a barrister and held the prestigious office of Treasury Solicitor. He and Caroline had no fewer than 12 children. John Dugdale was a clergyman and he and Charlotte had five children.

After her husband’s death Jane Forsyth continued to live in their home in Upper Wimpole Street, which she shared with her unmarried younger sister Kitty. She also spent much of her time at Broadstairs. Soon after the death the sale of Pierremont Hall was completed; it had been set in motion earlier in 1810 as Thomas’ health declined. In a press report dated 30 August it was indicated that ‘by private contract the whole of the premises may be had for £10,000.’ In 1809-11 Jane moved to another property nearby called the Maisonette. It is recorded that in 1826 the future Queen Victoria and her mother visited Pierremont Hall. Whether Jane Forsyth was invited to meet these illustrious ladies in her former home is not known.

The High Street in Broadstairs runs approximately due west from the sea. Pierremont Hall is on its south side. Opposite on the other side nowadays Belmont Road runs away to the north. To the east of the line of Belmont Road stood an elegant house in two acres of grounds called Masenet Cottage and later known as the Maisonette. In 1810 the house was approached directly from the High Street. The grounds, with their sea views, have disappeared under Belmont Road and its houses to the west and Wardour Close and its houses to the east. The current house is subdivided into flats, has no garden and is approached from Wardour Close. It is made up of two distinct parts. The northern part is a plain house in the Georgian style, while to the south there is a large extension with gabled roofs in the Victorian style. There can be little doubt that the extension was added after Jane lived there. Whether her husband bought the land and built the earlier part of the property at the same time as he built Pierremont Hall is not known but it is certainly a possibility. Jane died on 16 November 1835 at the Maisonette, having made her will on 3 March 1834 and an undated codicil in April or May 1834. On 16 May 1836, at the direction of her executors, there were auction sales at Broadstairs of, first, the contents and, secondly, the freehold of the Maisonette.

The fourth and final burial

Her will made no provision about burial but she must have thought that her wishes should be made clear to her executors, who were her sister Kitty and her friends George Maule and City merchant John Wood Nelson. The codicil is explicit: ‘I have now only to request that my funeral may be as plain as is consistent with my situation in life and that I may be laid with my dear friends at Ayott whose affection I experienced for so many years and if there is a space on the tomb stone for my name I would have it engraved there but no alteration to be made for that purpose.’

It was necessary for the executors to arrange for the coffin to be transported from Broadstairs to Ayot St Peter. The codicil anticipated this eventuality and made this special request: ‘As I have been in the habit of going to the Green Man Inn at Barnet for many years I request that my corpse rest there rather than in Town.’ It is not known whether a break in the journey of the coffin was made at the Green Man, which was a famous coaching inn located on the High Street in Barnet but is, sadly, no longer in business.

The burial was conducted by the new rector, Rev Charles Chester, on 27 November 1835. The register noted that the deceased had been brought from Broadstairs, that she was the relict of Thomas Forsyth Esq. and that her age at death was 80. Arrangements were made for these words to be added below her husband’s epitaph: ‘Here likewise are deposited the remains of Jane, relict of the above Thomas Forsyth Esquire, died Nov. 16th 1835.’

Conclusion

Jane Forsyth’s two male executors obtained probate of the will and codicil at Doctors’ Commons on 18 December 1835. Jane’s estate was sworn at under £40,000 in 1835, which is equivalent to perhaps £60 million in 2018. The will provided that Kitty was to be permitted to continue to have the use of 4 Upper Wimpole Street for three months after Jane’s death. Subject to this, her freehold and leasehold interests were to be sold and then the entire estate was to be distributed among some 18 relatives. She made specific provision for her domestic servants and left money for the ‘industrious poor’ of the parishes of Empingham, Rutland, and St Peter’s, Thanet, for ‘the Bathing Infirmary at Margate’ and for ‘the Scottish Hospital in Crane Court, Fleet Street, London.’ Jane Forsyth’s Empingham charity is still operational. The Margate infirmary was established in 1791; its buildings were open from 1796 until the hospital closed 200 years later in 1996. It was formally known as the Royal Sea Bathing Hospital and can claim to have been the first orthopaedic hospital in the world. It was on a tour of inspection of this establishment that the future Queen Victoria and her mother visited Pierremont Hall in 1826. As has been noted above, Thomas Forsyth was a ‘governor’ of the Scottish Hospital.

Kitty moved to a house called the Greenway in the hamlet of Shurdington in the Gloucestershire parish of Badgeworth. In 1841 she was sharing the house with her niece Harriet Blackman (who was a daughter of her brother John and had been married first to William Lawrence and then, after his death, to Dr James Blackman but was by 1841 again a widow) and Ann and Mary Seward. The four ladies had eight domestic servants to look after them. Kitty died there in 1845 aged 84 and was buried at Badgeworth parish church on 15 March. At the Greenway she was living close to William and Georgina Davy, whose home was on top of the Cotswolds at Cowley House. Both the Greenway and Cowley are nowadays smart hotels.

The four people buried under the Forsyth tomb in the old churchyard at Ayot St Peter all died without issue. It must be doubted whether any member of the Neale, Forsyth or Martin family has ever been to visit the tomb since the last burial in November 1835. This seems a poor return on what must have been a huge investment by Thomas Forsyth in their memorialisation, but at least one can say that their chosen final resting place is beautiful and peaceful over 200 years later. Let us hope that it remains so.

Peter Shirley, Ayot St Peter, 31 August 2018 (updated 4 December 2019 and 9 August 2021)

In writing this page I have been much assisted by the research efforts of Robyn Jacobs from Brisbane, and Mike Nason, who lives in Empingham, Rutland. I thank them both. An essay by Mike about Thomas Forsyth’s role as land agent for the Heathcote family can be viewed on the Empingham Local History website